Current Eyak Lake Projects

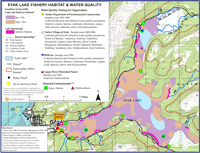

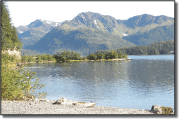

Situated between Prince William Sound, the Copper River Delta, and the Gulf of Alaska, Eyak Lake provides cornerstone habitat conditions for ten fish species. The adjacent fishing town of Cordova is home to subsistence, recreational, and commercial fishers whose livelihoods rely on the intact habitat of Eyak Lake’s freshwater ecosystem. Since salmon are the true currency of our community, their biological health directly translates into our region’s economic sustainability.

Girl Scout Troop 148 Cleans Up Eyak Lake Beach

Girl Scout Troop 148 took action in 2024 to clean up nails from pallet burning on Sunset Beach and secured donations to supply a fire ring and an educational sign. The fire ring’s purpose is to contain nails and debris from beach fires, keeping sensitive salmon spawning beds near the lake’s edge free from fire pollution.

This cleanup project was part of their Outdoor Journey to qualify for their Bronze Awards.

Copper River Watershed Project and the Forest Service donated funds to design and install the educational sign on Sunset Beach, incorporating sketches and words from the Girl Scout Troop.

What should you know about Eyak Lake?

Overall ex-vessel value of commercial harvest of Sockeye and Coho Salmon returns to Eyak Lake was estimated by Alaska Department of Fish & Game at $1,742,050 to $2,917,210, making Eyak Lake a multi-million dollar lake[1]. In addition to commercial harvest, Eyak Lake’s outlet river boasts one of the most popular sport fisheries in the Prince William Sound of Alaska. ADF&G reports an average of 10,181 Coho Salmon and 554 Sockeye Salmon were caught each year (2014-2016)[2]. Sustaining Eyak Lake’s fisheries requires unrestricted access to spawning and rearing habitat. Eyak Lake also provides other valuable recreation opportunities like canoeing and kayaking, and is a municipal water supply to the City of Cordova.

When the Alaska Coastal Policy Council recommended that Eyak Lake be designated an “Area Meriting Special Attention” (AMSA), a cooperative plan was commissioned by Professional Fishery Consultants. Authors Dick Groff and Ralph Pirtle compiled four years of data into the 1985 Cooperative Management Plan that drew out the AMSA boundaries and targeted bathymetry, lake bottom and vegetation, topography, and studies of the wildlife habitat.

When the Alaska Coastal Policy Council recommended that Eyak Lake be designated an “Area Meriting Special Attention” (AMSA), a cooperative plan was commissioned by Professional Fishery Consultants. Authors Dick Groff and Ralph Pirtle compiled four years of data into the 1985 Cooperative Management Plan that drew out the AMSA boundaries and targeted bathymetry, lake bottom and vegetation, topography, and studies of the wildlife habitat.

The goal of this plan was to develop objectives, policies, and actions:

- maintain and/or improve water quality of Eyak Lake

- maintain and/or improve the fishery production of Eyak Lake

- maintain and/or improve the wildlife habitat values associate with Eyak Lake

- accommodate existing and appropriate future residential, commercial, and facilities development within the planning area

- develop and maintain recreational opportunities and maintain the scenic values.

Ten species were found in the lake include:

- Humpback Whitefish

- Prickly Sculpin

- Stickleback

- Sockeye Salmon

- Coho Salmon

- Pink Salmon

- Cutthroat Trout

- Dolly Varden

- Eulachon

Sockeye and coho are the most abundant salmon found in the lake. From 1961 to 1981, aerial surveys showed a range from 463 to 28,366 sockeye spawners and 150 to 9,200 coho spawners in Eyak Lake. Pinks came in smaller numbers into the tributaries to Eyak Lake. Although five million chinook eggs were buried in Power Creek in 1921, rarely is a king found in Eyak Lake today.

Sockeye and coho are the most abundant salmon found in the lake. From 1961 to 1981, aerial surveys showed a range from 463 to 28,366 sockeye spawners and 150 to 9,200 coho spawners in Eyak Lake. Pinks came in smaller numbers into the tributaries to Eyak Lake. Although five million chinook eggs were buried in Power Creek in 1921, rarely is a king found in Eyak Lake today.

Professional Fishery Consultants conducted salmon studies in 1981 and 1982. The results for sockeye showed that 16% of spawners used Hatchery Creek and Power Creek, 8% used stream deltas, and the remaining 76% used gravel beaches along the shoreline, adjacent to inflowing streams. Sockeye rearing was primarily offshore in Eyak Lake, where zoo plankton is more plentiful.

Coho spawners were found in Hatchery Creek and Power Creek. They rear primarily in creeks and along the shoreline of Eyak Lake. Juvenile diets consisted of insects and snails.

CRWP, along with the Prince William Sound Science Center, ADF&G, and the Prince William Sound Keeper, have begun efforts to update this survey of spawning, rearing, and overwintering habitats. Our goals are to enhance Eyak Lake’s productivity and create awareness of habitat sensitivity when using the lake.

Click here to download the complete 1985 Eyak Lake AMSA Cooperative Report as a pdf.

PAST RESTORATION PROJECTS

Eyak Lake Restoration Projects

Since 2003, the Copper River Watershed Project has been coordinating partnerships and volunteer efforts to restore bank vegetation, fish passage, and water quality in Eyak Lake. Funding for these restoration efforts have come from NOAA’s American Recovery and Reinvestment act, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, National Fish & Wildlife Foundation, Alaska Coastal Management Program, and U.S. Forest Service/Chugach National Forest.

- bank re-vegetation work at avalanche zone and at Nirvana Park, 2003 and 2006;

- studied the presence of hydro-carbon pollutants in stormwater runoff draining into Eyak Lake;

- replaced 3 x 36″ culverts on Power Creek Road with one 58′ x 19′ x 6′ 1″ “stream simulation” culvert that facilitated stream sediment transport for replenishing spawning gravels in Eyak Lake;

- used American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) stimulus funds to remove an un-permitted spit and restore water circulation; reduce turbidity and hydrocarbons in Eyak Lake with installation of an oil and grit separator to filter Lake Avenue stormwater runoff; and

- analyzed City and Alaska Department of Transportation & Public Facilities snow management and storage practices to reduce snow melt pollution draining into Eyak Lake.

Power Creek Road Spit Removal

PROBLEM

Constructed in the 1960s; the spit was built to offer wave protection to a float plane dock, however this area is no longer used for this purpose.

ACTION PLAN

Excavated fill from the spit. A silt blanket was used in the October 2009 construction. The shoreline was revegetated.

OUTCOME

Improved lake circulation adjacent to the sockeye spawning beds and rearing habitat for cutthroats, coho juveniles, and sockeye fry.

Nirvana Park Oil & Grit Separator

PROBLEM

Stormwater emptied directly into Eyak Lake from the stormwater lines that drain Lake Avenue and the surrounding neighborhoods. This water brings with it high loads of sediment and hydrocarbons that can make life difficult for young salmon.

ACTION PLAN

Installed a Stormceptor Oil & Grit Separator to collect and separate out sediment and hydrocarbons before they enter the Eyak lake.

Worked with the City or Cordova and AK DOT to address snow storage practices to help keep unnecessary sand, salt and chemicals from entering the lake.

OUTCOME

Improved salmon rearing sites by flushing sediment buildup, reduced turbidity and decreased hydrocarbon input into Eyak Lake.

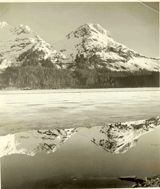

Nestled inside the Chugach National Forest sits a fresh water lake that has the shape of a three-armed starfish, diversity of many aquatic and land dwelling residents, and offers economy and recreation to the fishing town Cordova.

Nestled inside the Chugach National Forest sits a fresh water lake that has the shape of a three-armed starfish, diversity of many aquatic and land dwelling residents, and offers economy and recreation to the fishing town Cordova.

Eyak Lake is flat bottomed, average depth of eight feet, with very distinct stream channels cut one to twelve feet deeper than the surrounding bottom. This leads some to believe the area was once a tidal flat, draining out into Eyak River and/or Orca Inlet. However the lake was formed, certainly it has changed in many ways.

Copper River salmon fishermen remember the days before the 1964 Earthquake when they could pilot their bowpickers through Eyak River into Eyak Lake for mooring. Airplane pilots remember docking in Nirvana Lagoon. And some have shared stories of spruce canoes and the Eyak Native Village that stood where is now the Lake View Trailer Park.

The history of Eyak Lake, its citizens and their stories, are rooted very deep into Cordova’s culture today. Before 1900, a native fishing village of 200 called Eyak, dwelled along the shores of Eyak Lake. The name Cordova came from Cordova Bay, located at the head of Orca Inet.

The history of Eyak Lake, its citizens and their stories, are rooted very deep into Cordova’s culture today. Before 1900, a native fishing village of 200 called Eyak, dwelled along the shores of Eyak Lake. The name Cordova came from Cordova Bay, located at the head of Orca Inet.

HISTORY OF CORDOVA

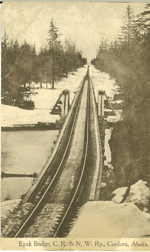

Michael Heney prospected Cordova as a port for copper mining in the Wrangell Mountains. After buying the old Pacific Packing Company cannery buildings for a headquarters and half of the one-quarter mile surveyed township, Heney began construction on the Copper River and Northwestern Railroad. From 1906 to 1911, 6,000 men worked building the railroad, while many came to Cordova to support that industry.

On July 8, 1909 Cordova was incorporated and a “Home Rule” government was approved. The community has and will continue to lead Cordova’s direction for growth. Industries have come and gone from Cordova. The rich copper mines of Kenicott, abundant harvests of razor clams, Vina Young’s

dairy farm, and countless entrepreneurial spirits have seen a home in Cordova. They came to build roads, schools, homes, and a town visitors and residents alike have come to love. And the one resource that has stayed with Cordova throughout the ages has been from the sea. Whether subsistence, sport, or for profit, fisherman have flocked to the bounty.

In 1917, Pioneer Packing Co. was built and many other processors followed in the 1920s. Many cannery names have entered the Cordova market, such as the New England Co., Western Fisheries Co., G.P. Halferty & Co., Alaska Packers Association, Sea Alaska Products, and Chugach Alaska Fisheries Morpac.

The export business was enormous for Alaskan salmon and many fisherman rose to supply that demand. In 1903, gas motors propelled the fishing boats in Alaska. From 1912 to 1960, seining gear size increased 257%.

Fishermen at Egg Island know the importance of a healthy run of sockeye. Their family, grocery store, mortgage company, and tax lawyer knows the importance; but how many knew that 50,000 of those come from Eyak Lake?

Fishermen at Egg Island know the importance of a healthy run of sockeye. Their family, grocery store, mortgage company, and tax lawyer knows the importance; but how many knew that 50,000 of those come from Eyak Lake?

HISTORY OF AVIATION

Another passion of Cordovans is aerodynamics. On May 7, 1929 Clayton Scott flew the first aircraft into Cordova. It was certainly not the last.

By 1934, Cordova constructed an airfield on Eyak Lake. Kirk Kirkpatrick began Cordova Air Service in 1934, Merle “Mudhole” Smith took over operations in 1939, Wayne Smith bought parts of it in 1968 and founded Chitna Air Service, Jim Foode purchased it in 1979. Tom Parker began Park Air. Other pioneers — Chisum Flying Service, Kennedy Air Service, and Ketchum Air — were the forerunners of today’s Alaskan Wilderness Air and Cordova Air.

HISTORY OF EYAK LAKE’S HATCHERY

In 1975, Patrica Roppel explored Alaska’s obsession with the disappearing salmon since the early 1900s. In 1871, Congress established the Commission of Fish and Fisheries in the United States to determine the cause of decreasing salmon runs. In 1889, fearful of Alaska’s destruction, they established the first Alaskan hatchery on Kodiak Island and made it unlawful to build any form of obstruction to bodies of water offering habitat to salmon. This was set throughout the state.

In 1975, Patrica Roppel explored Alaska’s obsession with the disappearing salmon since the early 1900s. In 1871, Congress established the Commission of Fish and Fisheries in the United States to determine the cause of decreasing salmon runs. In 1889, fearful of Alaska’s destruction, they established the first Alaskan hatchery on Kodiak Island and made it unlawful to build any form of obstruction to bodies of water offering habitat to salmon. This was set throughout the state.

The responsibility for salmon abundance was held with the federal government until the late 1890’s when government hatcheries were abandoned and cannery-operated hatcheries, wanting to protect their own stream and futures, flourished. This empowered the government, in 1900, to make it “mandatory for any person, company, or corporation taking salmon in Alaskan waters to produce sockeye fry in a last four times the number of mature salmon taken each year”. By 1902, the number was changed to 10 : 1.

After many failed operations, in 1906, the mandatory hatchery law was eliminated and a new rebate system ($.40 for every 1,000 fry released) was enacted with efficiency inspections biannually.

In 1917, the Alaska State Legislative set aside $80,000 for the Territorial Fish Commission, who had just moved operations from Juneau to Ketchikan, to build two new hatcheries. One was in Seward and the other, Eyak Lake.

In 1917, the Alaska State Legislative set aside $80,000 for the Territorial Fish Commission, who had just moved operations from Juneau to Ketchikan, to build two new hatcheries. One was in Seward and the other, Eyak Lake.

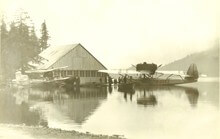

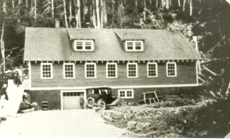

In June, 1921, AJ Sprague guided construction of not only a new hatchery but also roads, rails, bunkhouses, outdoor troughs, and a 1,400 foot pipeline to create a salmon pond. The first year, 12 million chinook eggs were taken, but because the egg baskets had not arrived, once the eggs were eyed, half of the eggs were buried into Power Creek and half into Spring Creek.

Sprague was fired by December, 1921 for frivolous spending on the hatchery. Edwin Wentworth succeeded in 1922 to plant 3 million sockeye eyed eggs at the head of Eyak Lake. In 1923, a new hatchery building was erected and methods became more sophisticated. Now able to rear fry, Wentworth released 3.8 million sockeye fry by January 24, 1924. The hatchery attempted to lengthen the rearing process in its 1924 egg take, however, the flood in August 1925, liberated the 3.2 million fry.

In the egg take of 1925, 7.3 million were released early by November, 1925. Funds had run out; with high expenses for heating, lighting, payroll, and running a predator control weir that destroyed any cuttrout trout or Dolly Varden from entering the lake. By 1926, the bunkhouse had burned and by 1927, the U.S. Forest Service took ownership of the hatchery. The old hatchery building became the Bethany Home for Children in 1938. Today only a bridge remains.

In the egg take of 1925, 7.3 million were released early by November, 1925. Funds had run out; with high expenses for heating, lighting, payroll, and running a predator control weir that destroyed any cuttrout trout or Dolly Varden from entering the lake. By 1926, the bunkhouse had burned and by 1927, the U.S. Forest Service took ownership of the hatchery. The old hatchery building became the Bethany Home for Children in 1938. Today only a bridge remains.

*** PHOTOS ON THIS PAGE ARE COURTESY OF THE CORDOVA HISTORICAL SOCIETY. ***